Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the cervical spine: a case report

Article information

Abstract

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a proliferative disease of the synovial membranes. Large joints are most commonly affected, while PVNS rarely affects the spine. We present a 70-year-old female patient with PVNS in the cervical spine who experienced both radiculopathy and myelopathy. An osteolytic lesion was observed over the sixth and seventh intervertebral foramina on the right cervical vertebrae on the radiological examination, and surgery was performed to remove the tumor and stabilize the cervical spine. Partial tumor resection was performed to preserve the right seventh cervical root. She was pathologically diagnosed with PVNS. After surgery, the patient's symptoms improved, and no recurrence was observed at outpatient follow-up 1 year later. In consideration of the recurrence rate, complete resection of the tumor is considered the standard treatment, but additional research is needed because there is no standard for adjuvant treatment in cases of incomplete resection or for methods to reduce the recurrence rate.

Introduction

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a rare benign disease of the joints that causes slow progressive proliferative process of the synovium of unknown etiology [1–3]. The appendicular skeleton, especially large joints such as the knee and hip joints are frequently involved, but PVNS involving the axial skeletal system is rare, typically involving the posterior elements [4]. It is important to be aware of this disease in the spine, because it can mimic malignancy, metabolic or inflammatory disease on radiologic examinations. In particular, elderly people have a high incidence of cancer, so if these lesions in the spine are confirmed by imaging tests, PVNS is more likely to be overlooked in diagnosis and treatment planning. In this paper, we report a case of a 70-year-old woman with PVNS of the cervical spine and try to review different epidemiologic, clinic, radiologic, and therapeutic features related to this pathologic entity.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman had complained of a 10-year history of gait disturbance, posterior neck pain, paresthesia and hypoesthesia to right upper extremity. Her symptoms worsened three months before admission. She had no antecedent trauma history. On the physical examination, the patient had mild tenderness of the paraspinous muscles bilaterally and exaggerated patellar reflex was observed. She had no motor weakness and no pathologic reflexes were observed.

Plain radiographs of the cervical revealed an osteolytic lesion of the right C6–7 lamina with marginal sclerosis (Fig. 1). Spine computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 2.6×3 cm well-circumscribed lytic bone lesion involving the right C7 lamina and vertebral body with sclerotic margins and cortical destruction (Fig. 2). On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images there was a large extradural mass involving the posterior elements of C6–7 vertebra, destroying the lamina, pars interarticularis, and transverse process. The lesion extended into the C6–7 right neural foramen and lateral aspect of the spinal canal with cord compression. The lesion was predominantly hypointense on T1 and T2-weighted images. After contrast medium administration, it showed inhomogeneous enhancement (Fig. 3). The decision was to operate the patient for both removal of the tumor and stabilization of the cervical spine. The patient underwent surgery via posterior approach. The first stage of surgery consisted on an osteosynthesis by lateral mass and pedicle screws ranging from C4 to T2, skipping the right C6, 7 screws because the tumor was situated at that level (Fig. 4A). The second stage focused on the removal of the tumor. The lesion was yellowish, extradural, and well differentiated from normal structures, seeming to originate from the right C6–7 facet joint. The right C7 root was encased by the tumor. To preserve the right C7 root, partial tumor removal was performed (Fig. 4B).

Preoperative cervical spine X-ray showing a osteolytic lesion at the right C6–7 level with marginal sclerosis.

Preoperative axial computed tomography scan demonstrating erosion of the right C7 lamina, pedicle, and vertebral body with sclerotic margins and cortical destruction.

(A) Preoperative sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing a tumor at the right C7 level. (B) Preoperative axial contrast enhanced T1-weighted MRI revealing a heterogeneously enhancing tumor involving the right C7 lamina, pedicle, and vertebral body compressing the C7 root, as well as the spinal cord.

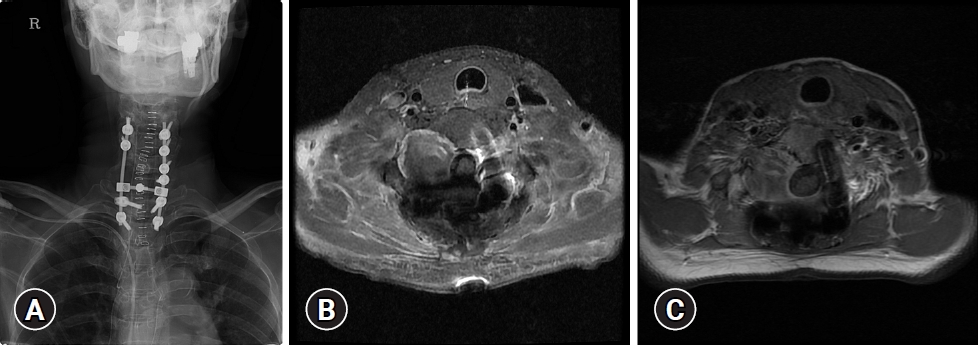

(A) Postoperative cervical spine X-ray showing a lateral mass and fixation of pedicle screws ranging from C4 to T2, skipping the right C6 and C7 screws. (B) Postoperative axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing a heterogeneously enhancing remnant tumor at the right C6/7 foramen area and resolution of the previous cord compression. (C) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI with 1-year follow-up shows no evidence of recurrence.

Postoperative, no major complications were noticed. The paresthesia and hypoesthesia to right upper extremity improved significantly immediately after surgery. Pathologic examination concluded to a PVNS (Fig. 5). At 1-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic and preoperative neurological discomforts such as paresthesia and hypoesthesia in the right arm and myelopathic gait were completely resolved, and no neurologic deficits were observed. Her follow-up MRI showed no gross change of remnant mass at right C6–7 intervertebral foramen area (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

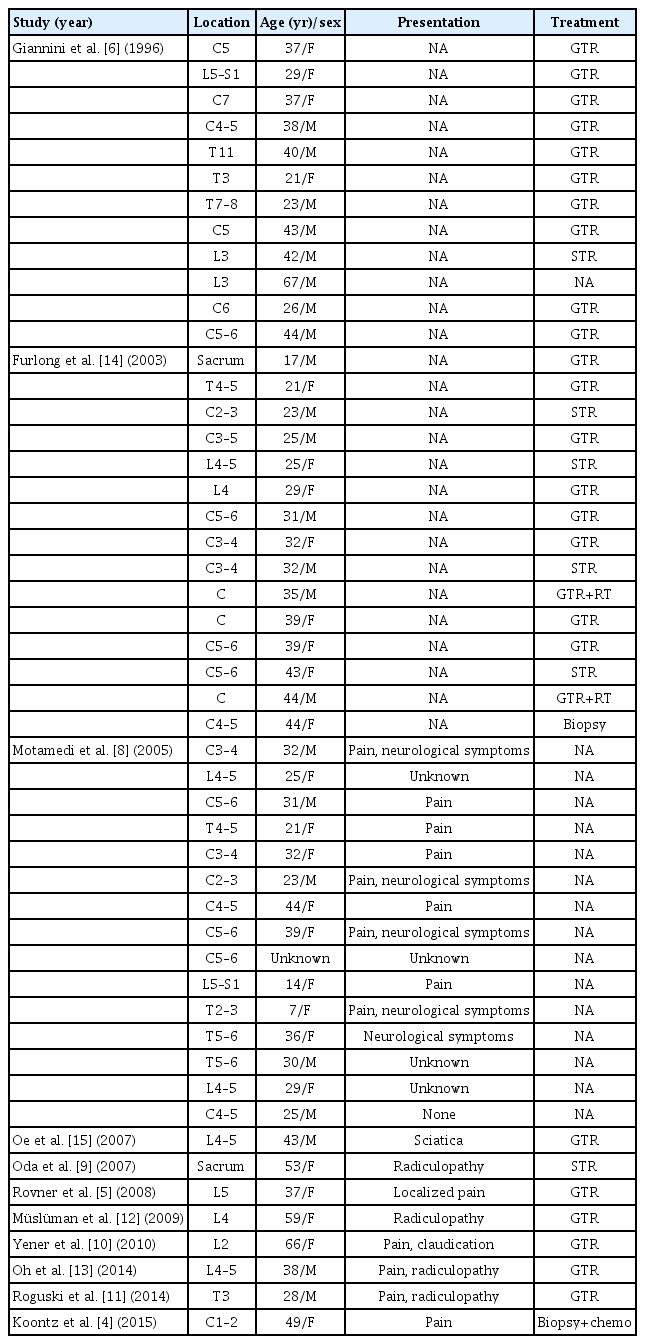

PVNS is a slowly progressive, benign, locally aggressive lesion distinguished by synovial proliferation associated with a hemosiderin deposition in the affected joint [1–3]. Knee, hips, and other weight-bearing joints are most affected, while less commonly PVNS can be found in the ankle, foot, wrist, shoulder, elbow, and tendon sheaths of the hand [5]. PVNS is seen to affect a wide range of age with no definite sex predilection, and polyarticular involvement is unusual [6,7]. Among all sites of PVNS involvement, PVNS involving the spine is very rare with the literature description limited mainly to small case series and a few case reports (Table 1) [4–6,8–15]. Therefore, the true incidence of PVNS involving the spine still remains uncertain. Based on the results of a small number of previous case series and case reports, Involvement of the cervical spine is reported most commonly with thoracic and lumbar involvement less common [6,8].

The etiology of PVNS is still debated. Minor trauma and repeat hemorrhage, inflammation, metabolic derangement, and neoplasm are considered possible etiologies of PVNS. However, in our case, it did not show any neoplasm-like propensity, and it was confirmed through outpatient follow-up. There are also studies in which the presence of inflammatory cells through pathological analysis considers the inflammatory response as the etiology of PVNS [9]. Minor trauma and the resulting hemorrhage are also mentioned as the etiology, but there is no statistical analysis, and there is no evidence to suggest that trauma is the cause in our case. There are various arguments for the etiology so far, but it is estimated that bias exists due to limited cases, and it is thought that the etiology can be diversified depending on the location of the onset, so a specific study on the spine is necessary.

Most of the major clinical symptoms are reported as pain with or without neurological deficits. Our patient experienced both myelopathy and radiculopathy. These symptoms were caused by compression or invasion of nerve elements, namely the spinal cord and roots.

Reports of general radiological features related to PVNS are mainly limited to the extremities, and there are insufficient reports of the spine [10]. According to the general radiographic characteristics of PVNS, bone destruction and sometimes an increase in synovial density due to hemosiderin deposition can be observed on plain radiographs [11]. CT can provide accurate information about the margins of the bone, and contrast-enhanced CT usually shows excessively dense mass of contrast-enhanced soft tissue, which can increase the diagnosis of disc herniation or bone erosion at first glance [16]. MRI is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of PVNS. It provides clear information about the margins of the lesion and the relationship of the mass to important neural structures. It shows low intensity signal of the mass on T1 and T2-weighted images, related to hemosiderin deposition [17]. However, since PVNS cannot be diagnosed only by imaging, differential diagnosis is required for primary bone lesions, extradural and mesenchymal neoplasm such as osteoblastoma, schwannoma, large cell lymphomas, fibrohistiocytic tumors and hypertrophic synovitis [10,12,13]. Metastatic bone tumors are also the most common bone malignancies and should be considered in differential diagnosis [11].

The therapeutic goal of spinal PVNS is gross total resection of the tumor with functional preservation, and to lower the recurrence rate [6,13,14]. Radiation therapy and radioisotope infusion, including surgical treatment, are discussed as treatment options [6,12]. Considering the tendency of PVNS with very rare metastasis and high local recurrence rate, the ideal treatment would be complete surgical resection, referring to most published treatment experiences [3,10,12,13,15]. Considering the high recurrence rate, some studies suggest postoperative radiation therapy, and other studies suggest radiation therapy as an adjuvant therapy for incomplete tumor removal [12,13]. In our case, despite incomplete resection of the tumor, radiation therapy was not performed as an adjuvant therapy. The patient's symptoms did not recur, and tumor progression was not observed on an outpatient MRI scan 1 year after surgery.

Conclusion

Since spinal PVNS is a very rare disease, it is easy to overlook in the differential diagnosis of spinal osteolytic lesions. Because of its many similarities to other neoplastic or non-neoplastic lesions of the spine, it is important to recognize this lesion, establish a diagnostic plan, and set the direction for treatment. The standard treatment for PVNS is total surgical removal, and the evidence for the effectiveness of radiotherapy as an adjuvant treatment is insufficient. We learned from this case that spinal PVNS is a rare but likely cause of lytic lesions of the spine. It is considered that additional studies are needed to establish the direction for postoperative treatment of spinal PVNS.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.