Intracranial pial arteriovenous fistula in a liver cirrhotic patient with esophageal varix

Article information

Abstract

Pial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is a rare cerebrovascular malformation. According to a series reported by Halbach, pial AVF accounts for 1.6% of all intracranial vascular malformations. Herein, we report a rare case of pial AVF in a 67-year-old male on medication for alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A) with esophageal varix, who presented with left-side motor weakness and mental fogginess. Digital subtraction angiography revealed contrast leakage in the left internal carotid artery and confirmed pial AVF. After angiography, brain computed tomography confirmed contrast leakage due to a ruptured fistulous point. Therefore, a Guglielmi detachable coil was placed and Onyx embolization to the fistula point was performed. In the present report, we describe this rare case and provide a review of the literature.

Introduction

Pial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is a rare cerebrovascular malformation. Intracranial pial AVFs have single or multiple arterial connections to a single venous channel. Pial AVFs differ from brain arteriovenous malformations in that they lack a true nidus. Pial AVFs differ from dural AVFs in that they derive their arterial supply from pial or cortical arteries that are not located within the dura mater. Because pial AVF has a poor natural history, clinical consideration of pial AVF followed by prompt appropriate treatment is important. We report a rare case of a 67-year-old male with intracranial hematoma caused by pial AVF along with a review of the literature.

Case Report

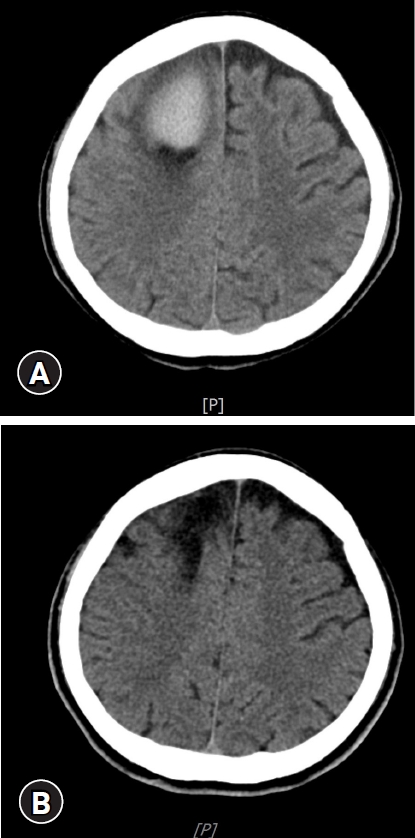

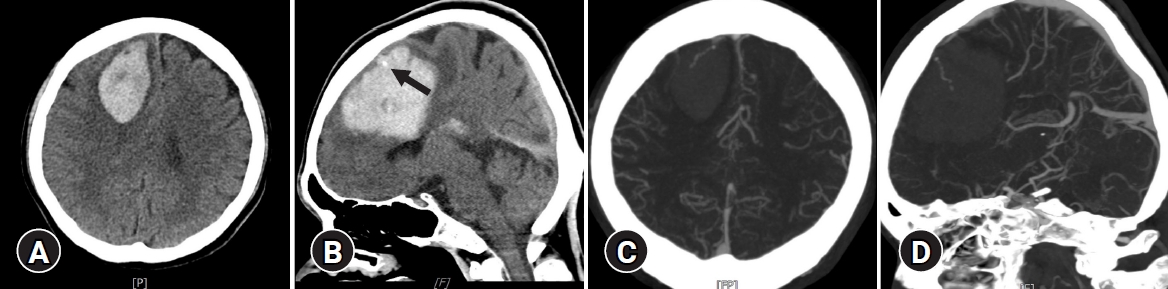

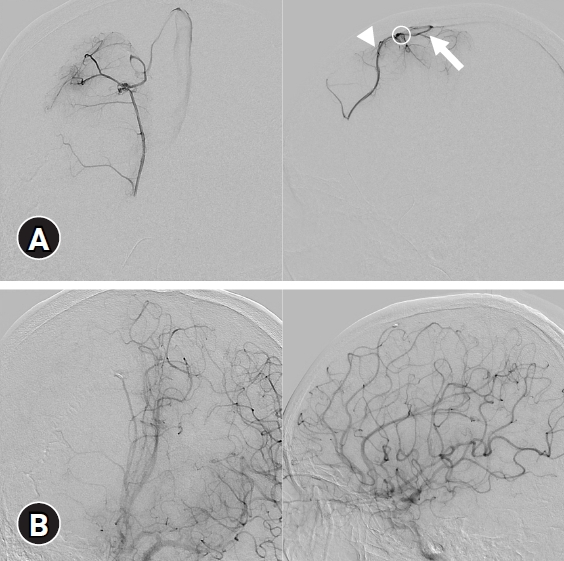

A 67-year-old male with a history of alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A) with esophageal varix presented to the emergency department with left-side motor weakness and mental cloudiness. He had been treated with conservative therapy at our hospital for alcoholic liver cirrhosis with esophageal varix. His past history included two surgical procedures for esophageal varices. Five hours before admission to our hospital, he was found unconscious in bed. The initial neurological examination revealed that he was in a drowsy state (Glasgow Coma Scale was E3M4V6) and left hemiparesis was noted. The platelet count was as low as 43,000, but coagulation factors were in the normal range. The lab values for liver function test were above the normal range (total bilirubin, 1.96 mg/dL; serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, 42.5 U/L; serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, 194.3 U/L). There was no history of head trauma or head injury. Brain computed tomography revealed the presence of an acute intracranial hematoma in the right medial frontal lobe with a significant mass effect (Fig. 1). The bleeding point was located just distal to the vein of the fistulous point (Fig. 1, 2A). Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed fistulous communication from the callosomarginal artery feeder draining into the vein with no intervening nidus (Fig. 2A). Under the diagnosis of pial AVF, Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) and Onyx embolization was performed. On postoperative DSA, the artery was well obliterated, and complete disconnection of the fistula was demonstrated (Fig. 2B). Surgical evacuation of hematoma was not performed after endovascular embolization. He had a high bleeding tendency due to underlying liver cirrhosis and decreased platelets at the time of admission. The patient recovered slowly, and after 1 month of rehabilitation (Fig. 3), he was able to return home with no focal neurological deficit, and he has been capable of performing day-to-day living activities ever since. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chosun University Hospital (IRB No: CHOSUN 2020-12-062). The patient provided written informed consent for publication of clinical details.

Computed tomography (CT) angiography showing an acute intracranial hematoma in the right medial frontal lobe and contrast leakage (A,B) (arrow) and drained into the vein (C,D).

(A) Digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Anterioposterior (left) and lateral (right) views from the arterial phase to the venous phase showing that the fistulous point (circle) was fed by the callosomarginal artery (arrowhead) and drained into the vein (arrow). (B) Postoperative DSA image showing excision of the pial arteriovenous fistula.

Discussion

Pial AVF accounts for 1.6% of intracranial vascular malformations and has a poor natural history [1,2]. Intracranial pial AVFs comprise a single venous channel in communication with one or more arterial connections from the pial or cortical arteries, and they lack a true intervening nidus, unlike cerebral arteriovenous malformations.

Pial AVFs can be congenital or result from a traumatic injury. Little is known about their pathophysiological mechanisms. Abnormal angiogenesis may play a role in the formation of pial AVFs [3]. Patients with pial AVFs usually present with headache, hemorrhage, seizure, or neurological deficits. Turbulence and increased pressure within draining veins may lead to the formation of giant varices. These dilated venous channels can exert a significant mass effect, compressing adjacent structures and impairing the cerebrospinal fluid pathway. Neurological deficits are often caused by the mass effect of the varix or by cerebral venous congestion and ischemia [4].

The patient in this study is currently on medication for alcoholic liver cirrhosis with esophageal varices and underwent two surgical procedures for esophageal varices. The patient presented with left-side motor weakness and mental cloudiness. Intracranial hemorrhage was observed on brain CT, and pial AVF was confirmed using DSA. It is possible that liver disease predisposes to both intracranial hemorrhage and thrombosis via a disordered and unstable coagulation system, as some studies have found an association between cirrhotic liver disease and venous thromboembolism [5,6]. If venous hypertension persists due to thrombosis, this could be another clue to the pathogenic mechanism. Because AVF patients with liver cirrhosis have a high probability of intracranial hemorrhage and infarction, active evaluation and treatment are required.

Venous varices commonly associated with AVFs are produced by the high turbulent flow caused by arteriovenous shunting. Shunt disconnection can be accomplished surgically or endovascularly [7,8]. In our case, GDC and Onyx embolization were performed. On postoperative DSA, the artery was well obliterated, and complete disconnection of the fistula was demonstrated.

Conclusion

Although pial AVF is usually asymptomatic, it may cause severe hemorrhage and neurological deficits that require endovascular and surgical treatment, especially in patients with liver problems. Because pial AVFs have a poor natural history and relatively good clinical outcome with prompt treatment, it is important to establish a clinical diagnosis. Once the diagnosis has been made, a neurosurgical and neuroendovascular team should determine the most appropriate treatment modality.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a research fund from Chosun University Hospital, 2020.